[Below is an excerpt from the autobiography of Eugene Sinowius Kordyban (1928-1996), transcribed by Mary A. Kordyban. It gives a good history of Galicia and Ternopil, as he learned it in gymnasium (Ukrainian school).]

All this was happening before the two World Wars in southwestern part of Ukraine, called by us Halychyna, with the accent on the last "a," but generally better known as Galicia, which had a history much different from the rest of Ukraine and, for that matter, different from any country known to man.

Once it was part of Kievan Ukraine, which was a powerful state in the

9th, 10th, and 11th centuries, but eventually, under continuous

pounding from the nomadic tribes and its own internal strife, it fell

apart. Galicia then became an independent state and existed for another

150 years, before being taken over by Poland. The rest of Ukraine

gravitated towards Lithuania and, when Lublin Union brought these two

countries into one kingdom, also came under Poland.

Once it was part of Kievan Ukraine, which was a powerful state in the

9th, 10th, and 11th centuries, but eventually, under continuous

pounding from the nomadic tribes and its own internal strife, it fell

apart. Galicia then became an independent state and existed for another

150 years, before being taken over by Poland. The rest of Ukraine

gravitated towards Lithuania and, when Lublin Union brought these two

countries into one kingdom, also came under Poland.

Under Poland, Ukraine suffered. The Polish landlords took over the land and Ukrainian noblemen, called boyars, found the loss of land and privileges less tolerable than the loss of nationality and Orthodox faith and rather quickly became polonized. The Ukrainians became serfs, property of the landlord.

Galicia, which was under Polish rule considerably longer, was considerably worse off, being the poorest and least educated part of Ukraine.

In 1648 the Khmelnytzky uprising against Poland affected Galicia only mildly and, though some of the battles were fought within its boundaries and many a Galician joined Khmelnytzky's Cossacks, when a treaty with Poland was signed, the autonomy was given only to Central Ukraine; Galicia was excluded. Eventually, Eastern Ukraine fell under the domination of Russian Tsars, but Galicia continued to be part of Poland.

And then there was the matter of religion. The Ukrainians had been Orthodox, subject to the Patriarch of Constantinople and as such suffered considerable persecution from the Catholic Poles. In 1596 a group of Ukrainian bishops signed a union with Rome retaining practically all of the rites and customs of the Orthodox Church and became known as the Uniates. Union was not accepted by all and much internal strife resulted. Eventually, most of Ukraine west of the Dnieper river, which was under Polish domination, became Uniate.

In the late 1700's came the partitions of Poland and, rather suddenly,

Galicia, after centuries of Polish domination, found itself in the

realm of the Austro-Hungarian Habsburg Monarchy.

In the late 1700's came the partitions of Poland and, rather suddenly,

Galicia, after centuries of Polish domination, found itself in the

realm of the Austro-Hungarian Habsburg Monarchy.

This was a tremendous change. Habsburgs became interested in these strange, poor people who were Catholics, yet worshipped God in a strange way; unlike the Latin in all Roman Catholic churches their Mass was in Old Slavonic. The Polish, familiar with the history of this church, and disappointed in the fact it did not become a polonizing influence, considered them second class Catholics, but Austrians had no such prejudices. They coined the phrase "Greek - Catholic" and organized seminaries for the proper training of priests.

Galicians did not call themselves Ukrainians at that time. The original Kievan Rus' eventually became known as Ukraine, but the Galicians considered themselves Ruthenians and this name persisted until the 2Oth century.

Despite of its many shortcomings Austro-Hungarian Monarchy was probably the most liberal country in Europe at that time and its many nationalities found life there quite tolerable, especially in view of the fact of what followed it.Although the official language was German, local languages were not only tolerated, they were allowed a reasonably free development. Serfdom was abolished in 1848 and what followed was a growth of education and culture among the Galician Ukrainians. The Galicians became acquainted with the free, though far from perfect, election system and general public education. Although classes of society still existed and nobility carried with it certain privileges, the classes were not frozen anymore. A poor and illiterate peasant found that, by scrimping and starving and perhaps selling a piece of his land, he was able to send at least one of his sons through college, so that he could become a lawyer, a priest, or a doctor and break the invisible bonds of being a "stinking" peasant.

A new class formed known as "intelligentsia" which began to challenge the old nobility for leadership of the country. They, in fact, quickly began to leave the noblemen behind, since the latter were used to easy living and were more interested in trips abroad than in the rigors of higher education.

Initially, the peasants' sons, having achieved a higher status in life,

were ashamed of their origins and avoided any connection with their

relatives to the point of even using Polish in their conversations,

since this appeared to be a more noble language. As their numbers

grew, however, enough brave and honest souls were found who realized

that they owed their status to the sacrifices of their peasant

parents. In trying to repay this they turned their efforts

towards betterment of the life of the peasants. The peasants' lot

at that time was not an enviable one, mainly because some 85% of the

population in Galicia were peasants and the land was scarce. Both

in their political and family life the Ukrainians have a flaw which has

always created a problem for them. Both the Ukrainian princes and

peasants considered that, if they had several children, their property

must be divided more or less equally among them.

Initially, the peasants' sons, having achieved a higher status in life,

were ashamed of their origins and avoided any connection with their

relatives to the point of even using Polish in their conversations,

since this appeared to be a more noble language. As their numbers

grew, however, enough brave and honest souls were found who realized

that they owed their status to the sacrifices of their peasant

parents. In trying to repay this they turned their efforts

towards betterment of the life of the peasants. The peasants' lot

at that time was not an enviable one, mainly because some 85% of the

population in Galicia were peasants and the land was scarce. Both

in their political and family life the Ukrainians have a flaw which has

always created a problem for them. Both the Ukrainian princes and

peasants considered that, if they had several children, their property

must be divided more or less equally among them.

In the Kievan Rus' this division of the state among the princes, who were in theory supposed to respect the superiority of the prince of Kiev contributed in no small measure to the downfall of that state.

In the case of the peasant, the land was divided into small narrow strips so that eventually a great percentage of the peasants own so little land that they could barely survive. Furthermore, the land they owned was not all in one piece, but rather in strips scattered over the vicinity.

The efforts of the intelligentsia to help the peasants took several forms. First, by studying the law of the land, they could assure that the peasants' voting rights and other civil rights were protected. Secondly, they attempted to improve the farming method and general education of the peasants. Finally, by organizing farming cooperatives they tried to assure that the farmers would obtain a fair price for their product.

It is in this last effort that they ran into conflict with the Jewish population since they were the ones that controlled the trade. There was a great deal of Jews in Galicia, very few in the villages, but in most of the towns and cities the Jews amounted to about 1/3 of the population. There were quite a few Jewish doctors and lawyers on one hand, some workers and teamsters on the other end of the spectrum, but the majority of them were involved in some type of trade. Most of the stores in our neighborhood were owned by Jews. I particularly remember two small grocery stores, side by side, owned by brothers Klar. Before my time this was a larger store owned by their father, but after his death, the brothers quarreled and split the store in half. This also split the customers forever and you either frequented one store or the other, but never both. Over the years the customers developed a considerable loyalty toward a particular store and it was considered almost an act of treason to shop even once in the competitor's store.

Many Jews lived in a compact area of our town, but nobody ever used the word "ghetto." The rest were scattered throughout the town. There were many nasty remarks made in conversation about the Jews in general and one could see the words "Beat the Jews" appearing on the walls, but as far as I knew, nobody ever beat anybody and there were rather friendly relations between Jews and non-Jews.

When the cooperative movement came, it became of necessity directed against the Jewish merchants, but again, there was no violence, just competition. The cooperatives, under the slogan "Buy your own merchandise from your own"; claimed to have better, fresher and cleaner products at competitive prices and it made considerable inroads into the commerce of our city.

Anyway, the Jews were not our main problem. Austrian Empire was divided into lands, somewhat like states, each with a certain amount of autonomy. When Austria obtained Galicia during dismemberment of Poland it also obtained part of Southern Poland which included the city of Cracow; they combined it all into a land and called it Galizien. It contained more Poles than Ukrainians and this always created difficulties for Ukrainians. Most of nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century consisted of continuous struggle against Polish domination.

At first the Ukrainian language was considered a peasant's talk and the

books by Ukrainian writers were written either in Polish or in old

Slavonic. Then, in the middle of the 19th century a young priest named

Shashkevych published a small book of poems written in the peasants'

tongue. This was almost a heresy and created quite a stir, but it also

opened the floodgates and brought a flowering of Ukrainian literature.

The "Ruthenian" language now became equal to the rest in the Austrian

empire. I am writing Austrian, rather than Austro-Hungarian, because

internally the empire was firmly divided between Austria and Hungary.

While Austria permitted a rather free development of individual

nationalities, there was a great deal of oppression under Hungarian

rule, as in the case of Slovaks and the Ukrainian south of Carpathian

mountains who had the misfortune to belong to that part of the empire.

I was born 10 years after the demise of the Austro-Hungarian empire and

yet I heard so much about it from my parents and people around me that

I almost have a feeling like I actually lived in those times. Just how

free the life was in those days may be shown by this example which my

father used to tell me about. Every larger city had its own

regiment of troops and as the troops marched out daily for their

training outside of town, little boys ran along them chanting to the

beat of the drums: "At Aspen, Wagram, Austerlitz we got our ass kicked

and did not say a word." As one with a knowledge of European

history would recall, those were the major battles in which Austrians

got beaten by Napoleon at the end of the 18th century. Even in

America one would hesitate to mock the marching troops in this

manner. Actually it was forbidden by law to be disrespectful to

the person of Kaiser and his family, but the prime minister and other

members of the parliament were fair game for criticism.

At first the Ukrainian language was considered a peasant's talk and the

books by Ukrainian writers were written either in Polish or in old

Slavonic. Then, in the middle of the 19th century a young priest named

Shashkevych published a small book of poems written in the peasants'

tongue. This was almost a heresy and created quite a stir, but it also

opened the floodgates and brought a flowering of Ukrainian literature.

The "Ruthenian" language now became equal to the rest in the Austrian

empire. I am writing Austrian, rather than Austro-Hungarian, because

internally the empire was firmly divided between Austria and Hungary.

While Austria permitted a rather free development of individual

nationalities, there was a great deal of oppression under Hungarian

rule, as in the case of Slovaks and the Ukrainian south of Carpathian

mountains who had the misfortune to belong to that part of the empire.

I was born 10 years after the demise of the Austro-Hungarian empire and

yet I heard so much about it from my parents and people around me that

I almost have a feeling like I actually lived in those times. Just how

free the life was in those days may be shown by this example which my

father used to tell me about. Every larger city had its own

regiment of troops and as the troops marched out daily for their

training outside of town, little boys ran along them chanting to the

beat of the drums: "At Aspen, Wagram, Austerlitz we got our ass kicked

and did not say a word." As one with a knowledge of European

history would recall, those were the major battles in which Austrians

got beaten by Napoleon at the end of the 18th century. Even in

America one would hesitate to mock the marching troops in this

manner. Actually it was forbidden by law to be disrespectful to

the person of Kaiser and his family, but the prime minister and other

members of the parliament were fair game for criticism.

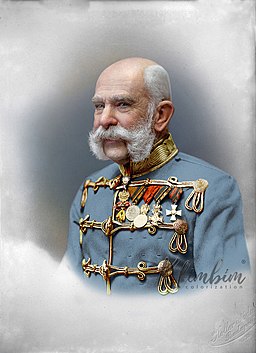

Over a large portion of the last century and well into the First World

War the Kaiser was Franz Joseph I who distinguished himself mainly by

his longevity. He was, however, greatly respected by Galician

peasants, who believed that he loved them dearly and, if there were any

laws that were passed of a disadvantage to the peasants, they said it

was the noblemen advisors that did them. It was told that many a

peasant set out on foot for Vienna to see the Kaiser personally and to

explain to him the suffering of the peasants, but I have heard nothing

of the outcome of such pilgrimages. Kaiser Franz Joseph outlived

his son and closer relatives, so that Ferdinand, a somewhat more

distant relative, became the Crown Prince. He was considered

liberal and friendly to the Ukrainian cause. The Ukrainians hoped

that upon ascension to the throne he would join all Ukrainian

territories under Austria into one land where they would have a clear

majority and would be permitted to develop freely. These hopes

were dashed in 1914 when a Serb, Gavrilo Princip, assassinated

Ferdinand at Sarajevo. What appeared to be at first a primitive

action against Serbia turned into the First World War which brought the

end to the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and severely brutalized our little

comer of the world.

Over a large portion of the last century and well into the First World

War the Kaiser was Franz Joseph I who distinguished himself mainly by

his longevity. He was, however, greatly respected by Galician

peasants, who believed that he loved them dearly and, if there were any

laws that were passed of a disadvantage to the peasants, they said it

was the noblemen advisors that did them. It was told that many a

peasant set out on foot for Vienna to see the Kaiser personally and to

explain to him the suffering of the peasants, but I have heard nothing

of the outcome of such pilgrimages. Kaiser Franz Joseph outlived

his son and closer relatives, so that Ferdinand, a somewhat more

distant relative, became the Crown Prince. He was considered

liberal and friendly to the Ukrainian cause. The Ukrainians hoped

that upon ascension to the throne he would join all Ukrainian

territories under Austria into one land where they would have a clear

majority and would be permitted to develop freely. These hopes

were dashed in 1914 when a Serb, Gavrilo Princip, assassinated

Ferdinand at Sarajevo. What appeared to be at first a primitive

action against Serbia turned into the First World War which brought the

end to the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and severely brutalized our little

comer of the world.

While the Ukrainians under Austria were permitted a relatively free cultural and political development, the rest of Ukraine, "Great Ukraine", as we called it, was under Tsarist Russia and suffered greatly. The serfdom was not abolished until 1861 and even then the peasants were still dependent on the landlord. The illiteracy among them was close to 90%. Still, Ukrainian literature developed and began to flourish bringing with it the thoughts of independence. In the latter part of the 19th century, however, a law was passed which claimed that "there never was, is not now and never will be such a thing as a Ukrainian language" and forbade printing any material in this non-existent language. Thus in a little over one hundred years Galicia, the most backward part of Ukraine, became the freest and culturally most advanced part. Piedmont of Ukraine, some called it after a state that united Italy. The books of authors, forbidden in Russia, were freely published in Galicia and a number of cultural leaders from the central Ukraine came to Galicia to work in freedom.

My home town, Ternopil, a city of about 35,000 population is situated

in the northeastern part of Galicia, some 60 km. west of the river

Zbruch which was the boundary between the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and

the tsarist Russia. Founded by Count Tarnowski in the 1500's it

became an important trading and administrative center. It had to

withstand some Tartar attacks, but generally did not figure prominently

neither in the history of Ukraine, nor that of Poland. During

Austrian occupation Galicia was divided into three major administrative

units with Ternopil being the capital of one of them. With the

coming of the railroads it became also an important railroad

center. Located in the midst of a rich agricultural area it was

also a trading center, but had very little industry. There were

two brick factories, some breweries and flour mills and later a

cigarette paper factory and sugar refinery. The worker population

then was relatively small. Most were clerks, small artisans such

as tailors, shoemakers, blacksmiths and others, there were many

shopkeepers and a number of farmers who usually lived on the outskirts

of town, but still were definitely considered the townspeople.

My home town, Ternopil, a city of about 35,000 population is situated

in the northeastern part of Galicia, some 60 km. west of the river

Zbruch which was the boundary between the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and

the tsarist Russia. Founded by Count Tarnowski in the 1500's it

became an important trading and administrative center. It had to

withstand some Tartar attacks, but generally did not figure prominently

neither in the history of Ukraine, nor that of Poland. During

Austrian occupation Galicia was divided into three major administrative

units with Ternopil being the capital of one of them. With the

coming of the railroads it became also an important railroad

center. Located in the midst of a rich agricultural area it was

also a trading center, but had very little industry. There were

two brick factories, some breweries and flour mills and later a

cigarette paper factory and sugar refinery. The worker population

then was relatively small. Most were clerks, small artisans such

as tailors, shoemakers, blacksmiths and others, there were many

shopkeepers and a number of farmers who usually lived on the outskirts

of town, but still were definitely considered the townspeople.

The old town was surrounded by walls, but these were taken down long ago and the town spread considerably beyond them. Only such remainders as Wall Street remained, as well as the appearance of churches and synagogues near the walls which were used as battlements.

The city's population consisted of almost three equal parts, Ukrainians, Poles and Jews with the Jewish population slightly larger than the others. The nationality coincided with religion, Ukrainians were Greek-Catholic, Polish were Roman Catholic, and, the Jews, were of course, Jewish. There may have been some German Lutherans and a few Ukrainian Orthodox, but I never met any. There also were some Protestant sects whom the general population considered weird, whispered about their strange religion and called them baptists, although they probably were not that. The religious preferences were so strong that they were automatically identified with nationality, so that a Jew who decided to be baptized, became a Pole or a Ukrainian depending on the rite he accepted and an official act of changing from Ukrainian to Polish was to transfer your vital records from Greek-Catholic to a Roman Catholic office, an act which became especially significant when Poland occupied Galicia after the First World War.

Kordyban is basically not a Ukrainian name and I have never met anybody by that name either among Ukrainians, or among many people of other nationalities whom I met in my life. My mother called my father jokingly a gypsy and told me that his grandfather appeared one day from somewhere with a good deal of money, bought farm land, and settled in the city. He was somewhat darker than the local population and had a prominent nose. After becoming integrated into the society he married a local girl and had several children. One of his sons emigrated to America sometime near the end of the 19th century, so it is possible that there are some other Kordybans in this country. Every time I come to some city I always look through the telephone book, but I have not discovered them yet.

Powered by w3.css